Royal Academy of Arts Magazine, London

Article

2025

émergent, London

Interview

2025

C-Mine, Genk

Exhibition Text

2025

Hannah Barry Gallery x Foolscap Editions, London

Editor

2025

Lo Brutto Stahl, Paris & Basel

Exhibition Text

2024

Hannah Barry Gallery x Foolscap Editions, London

Editor

2024

émergent, London

Interview

2024

DUVE, Berlin

Exhibition Text

2024

émergent, London

Interview

2024

Incubator, London

Exhibition Text

2023

QUEERCIRCLE, London

Exhibition Text

2023

L.U.P.O., Milan

Catalogue Essay

2023

Tarmac Press, Herne Bay

Catalogue Essay

2023

Brooke Bennington, London

Exhibition Text

2023

Freelands Foundation, London

Catalogue Essay

2023

superzoom, Paris

Exhibition Text

2023

Lichen Books, London

Catalogue Essay

2022

Tennis Elbow, New York

Exhibition Text

2022

émergent, London

Interview

2022

— Extract —

Charlie Mills: Hélio-centricities was also deeply connected to the site in which it was created. It featured black panels that appropriate the space’s own helioscreens – what you call the “membrane” of the house – as well as stained-wood benches reappropriated from the actual garden space. These elements reference not only the work of Oiticica but the energy and contradictory impulses of the building’s modernist architecture. What was most interesting to you about the site in which you were working?

Tom Burr: I was living in the house while in São Paulo, in a bedroom on the second floor above the exhibition spaces and looking out on the back garden. Everything was right there in the same building. This highlighted the fragile division between my personal and professional realms and laid it out in architectural terms. I began to think about exposure. About being seen, and exposing myself to a public. The house is in a modernist style and was designed to be highly protectionist to the public street side, with multiple walls and gates and fewer windows, and very open to the back private garden. It’s a fairly anxious piece of architecture, heavily guarded, which was motivating for me and in sync with my thoughts.

This unclear distinction between private and public has echoed throughout your practice – not only in your sculptures but your textile works too, which themselves oscillate between the personal – the confessional, almost – and that which is revealed or presented to an audience. What first led you to an interest in this dynamic? This tension between participation and concealment?

I think that this is the result of being more focused on making exhibitions, more than I am in creating any discrete or isolated object. I’m concerned with the whole field, in a sense. I think about what is seen and what isn’t, who is seen and who isn’t. And what exposure means both for the viewer and the viewed. It also stems from considering how subjectivities are concealed or revealed and made to perform or to remain withdrawn, and that there is no intrinsically private realm that isn’t linked to a public one.

Several of your iconic works from the mid-90s — such as Circa ’77, An American Garden, 42nd Street Structures — draw on this tension between private and public. Importantly, their prescience comes from revealing not only the tension but the plurality of this dynamic — between different privates and publics. Can you explain a bit more about this plurality and why you want this idea to resonate in your work?

With these works I was really trying to convey a kind of fragmentation of subjectivities; the idea that many layers, many factors, many determinations are embedded in a body. And likewise with the social body, this is best described as being in a state of flux and plurality, as you say. With these works specifically, I was thinking about how the concept of a “general public” negates or disappears the existence and experience of queer bodies, or more specifically, gay male bodies who have used parks, movie theatres and other spaces as both refuge and a site of pleasure and connection. With An American Garden, as one example, I wanted to present the layers of publics in one specific physical space, the Ramble in Central Park, with different interests and stakes in that same plot of land, and how these different stakes are deeply intertwined with one another and produce a complex political and spatial landscape. This work came out of Robert Smithson’s writing as well, in particular his last essay, Frederick Law Olmsted and the Dialectical Landscape (1973), which was about the Ramble, and that link made me think about social space and physical landscapes as texts, with multiple readings, subtexts, footnotes, etc.

With Circa ’77 I also thought about physical sculpture as a sort of text, with multiple voices embedded in the same site. Power dynamics at work. I like this as a model. We look at artworks, we take them in, and we also read them. I was also exploring concepts of displacement, and of an external site’s relationship to the exhibition site of a gallery or museum and how to inscribe this shift of place into the work. All of the works you mentioned were pointing to specific locations external to the spaces that the works were shown in. I wanted to create parallels between that external site — Times Square for instance, with 42nd Street Structures — and the gallery where the work was exhibited, to collapse those different publics or audiences onto each other so that the dynamics I was pointing to would resonate as present and “here” — not simply “out there.”

Do you think these ideas have changed since you were working in the mid-90s to today?

I’m still navigating all of this with my work. Contemporary culture continues to change of course, now isn’t the same as then. But the idea of fragmentation in relation to my own subjectivity and to others feels politically important as an armature for thinking, as a way of pushing back in some sense against normalising forces which aim to control bodies and thought. It also can bring extreme pleasure, it seems to me. And different forms of pleasure are always at risk of being shut down.

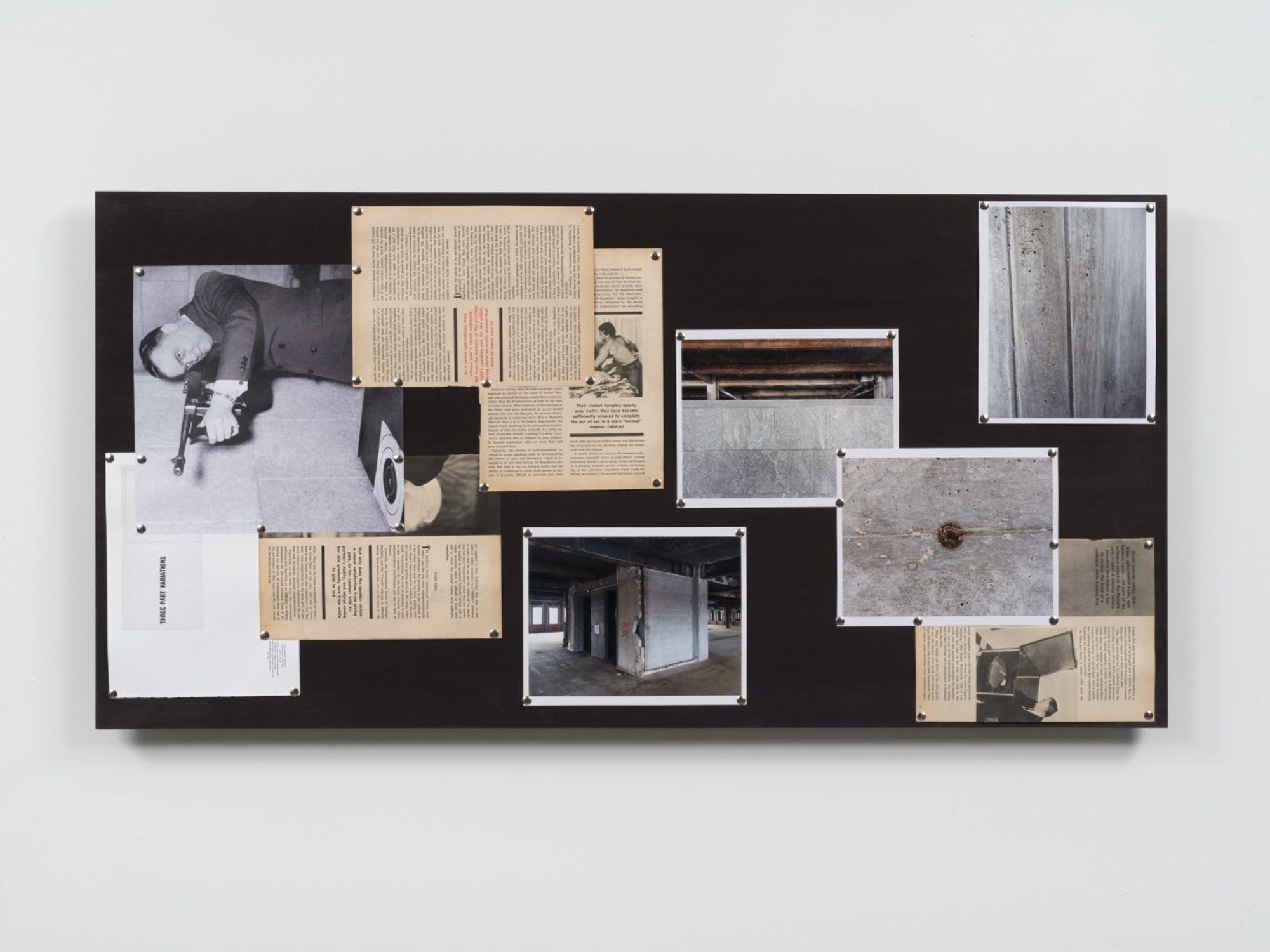

You mentioned the idea of “displacement” – which is also a core motif in your work – and the rise of neoliberalism that took place after the post-war consensus has certainly intensified feelings of displacement throughout cities across the world. When I look at your work, I feel this sense of deracination – or “uprooting” – of particular places and their histories. In particular, your work Body/Building in New Haven in 2017. Can you tell us a bit about this work?

New Haven is where I was born and grew up, if that means anything in relation to your question about uprootedness and displacement. With Body/Building I was digging autobiographically, self-consciously so, thinking about my experience there. More interestingly, I was fleshing out a simultaneity of experience hovering around the geographic area and the year 1970, when the Marcel Breuer building, where the project took place, was first built. So much happened there at the time that remains embedded in the place and part of its structure: design history, urban developments, political events — including the Black Panther trials and the public protests that surrounded them.

The French novelist and poet, Jean Genet was there and a part of it as well, writing his eloquent speech in support of the Black Panther Party; the FBI was tracking Genet’s every move, as part of their surveillance of the Panthers. The building was a witness to all of that, as well as one of the actors. Body/Building existed for one year in this abandoned Breuer building, which was then owned by Ikea. They didn’t know what to do with it so they let us in, allowed us to squat there and create this durational thing. The structure became a stage were several characters converged in a constellation across the space: Jim Morrison, Anni Albers, Jean Genet, J. Edgar Hoover, Breuer, Brutalism, etc.

You have spoken in previous interviews – and it can be seen in your work – of the formal influences of artists such as Tony Smith and Sol LeWitt. However, when looking at your work – particularly recent shows such as Put Down (2016) and Surplus of Myself (2017) – it is another generation of artists, particularly those who queer minimalist phenomenologies in the late 60s, 70s and 80s that come to mind (Bruce Nauman, Félix González-Torres, Eva Hesse). There is a work by Bruce Nauman called Henry Moore Bound to Fail (1967) that I would love to know if you have ever seen and what you think of it – it seems so relevant to what you are doing with your clothing pieces.

The minimalists were material for me, a place to start and to react to. Both formally and also as a social group, a social force. I was less interested in the aesthetics and more in the politics and implications of reduction, as well as the close associations with architecture and emblems and motifs of containment. The other artists you name represent a wide swath of history. Eva Hesse was probably my strongest high-school art crush and fueled a lot of my thinking at the time, spatially, and materially. Also a Capricorn. Bruce Nauman is a curious figure whose work has always drawn me, it's often stranger than you first think. His corridors and his contrapposto studies are excellent, deceptively simple works that demonstrate power in its latent forms, and I relate to that thinking. You’re the first person to make that connection. And now I will go look up the Henry Moore piece you mention.

But with Félix it's different. He was six years older than me but we were friends and peers in the late 1980s in New York and some of the conversations we had at that time helped me begin to navigate the then burgeoning interconnection between art making and the market which felt so overwhelming at the time. Of course it's only increased since then. We also shared a commitment to working with the entanglement of form and power, and to consider form in its ideological dimensions. We were both young queer artists — gay men — living through the battleground of the AIDS crisis, which ultimately had a profound effect on both of our work, and which, of course, took Félix’s life.

Félix and I exhibited together again recently, each with a large scale work — his Untitled (Water) and my Deep Purple — as part of Jared Ledesma’s 'Queer Abstraction' exhibition at Des Moines Art Center in 2019. The spatial play of the two works together, each with their own intrinsic meanings and histories, along with their shared turning and twisting of monochromatic painting, was gratifying for me to experience on a number of levels; like a dialogue that has continued over time, a form of resilience.

Guts Gallery, London

Exhibition Text

2021

Kupfer Projects, London

Exhibition Text

2021

Collective Ending, London

Catalogue Essay

2021

L21 Gallery S’Escorxador, Palma De Mallorca

Exhibition Text

2021

TJ Boulting, London

Exhibition Text

2021

COEVAL, Berlin

Interview

2021

Quench Gallery, Margate

Exhibition Text

2021

COEVAL, Berlin

Interview

2021

COEVAL, Berlin

Interview

2021

Foolscap Editions, London

Catalogue Essay

2020

Gentrified Underground, Zurich

Catalogue Essay

2020

Camberwell College of Arts, London

Exhibition Text

2019

Kronos Publishing, London

Editor

2019

Elam Publishing, London

Editor

2019

William Bennington Gallery, London

Catalogue Essay

2019

Elam Publishing, London

Catalogue Essay

2018

Camberwell College of Arts, London

Exhibition Text

2018

Limbo Limbo, London

Exhibition Text

2017

Saatchi Art & Music Magazine, London

Review

2017

B.A.E.S., London

Exhibition Text

2016