Royal Academy of Arts Magazine, London

Article

2025

émergent, London

Interview

2025

C-Mine, Genk

Exhibition Text

2025

Hannah Barry Gallery x Foolscap Editions, London

Editor

2025

Lo Brutto Stahl, Paris & Basel

Exhibition Text

2024

Hannah Barry Gallery x Foolscap Editions, London

Editor

2024

émergent, London

Interview

2024

DUVE, Berlin

Exhibition Text

2024

émergent, London

Interview

2024

Incubator, London

Exhibition Text

2023

QUEERCIRCLE, London

Exhibition Text

2023

L.U.P.O., Milan

Catalogue Essay

2023

Tarmac Press, Herne Bay

Catalogue Essay

2023

Brooke Bennington, London

Exhibition Text

2023

Freelands Foundation, London

Catalogue Essay

2023

superzoom, Paris

Exhibition Text

2023

Lichen Books, London

Catalogue Essay

2022

Tennis Elbow, New York

Exhibition Text

2022

émergent, London

Interview

2022

Guts Gallery, London

Exhibition Text

2021

Kupfer Projects, London

Exhibition Text

2021

Collective Ending, London

Catalogue Essay

2021

L21 Gallery S’Escorxador, Palma De Mallorca

Exhibition Text

2021

TJ Boulting, London

Exhibition Text

2021

COEVAL, Berlin

Interview

2021

Quench Gallery, Margate

Exhibition Text

2021

COEVAL, Berlin

Interview

2021

COEVAL, Berlin

Interview

2021

Foolscap Editions, London

Catalogue Essay

2020

Gentrified Underground, Zurich

Catalogue Essay

2020

Camberwell College of Arts, London

Exhibition Text

2019

Kronos Publishing, London

Editor

2019

Elam Publishing, London

Editor

2019

William Bennington Gallery, London

Catalogue Essay

2019

The Matter of Memory

'Memory in action is not a dead deposit; it is a living and functional focusing of energies. It is life at the acme of attention, creation and decision. Memory is the living reality, the past felt, those moments of heightened consciousness which we feel as suggested opportunities to make the future.'

– Henri Bergson, Creative Evolution, 1911

— Extract —

Over the past two years, Simon Linington has embarked upon a sequence of exhibitions that continue to elicit many of his key conceptual nuclei, further establishing his practice – be it implicitly or explicitly – with the corollary propositions of time’s own relativity. In doing so, Simon has formalised a series of motifs and techniques for extrapolating often nebulous and wrought subject matters – the everyday, the ephemeral, the excluded – refracted through the prism of what he serenely dubs, ‘the story’. To articulate it differently, these were works that embodied the procession of time untethered from is myopic Kantianism – the isolated world view that time is nothing but a single fixed constant, progressing ad infinitum along its narrow-cobbled path to eternity. It would seem to me that Simon’s works were wrestling with a very different conception of time – important questions that sprung from the intellectual fallout of Einstein’s seminal discovery. How – if time is relative – do we come to experience ourselves as temporal subjects? How is it that we perceive and experience a past, present and future, when in reality these are all but one and the same, caught in perennial flux?

Representing a pitch-shift from his previous bodies of work, Simon began his series of exhibitions in early 2017 at Division of Labour, Herald Street, with a self-effacing and intuitive architectural work named Everything Can Be Broken, transforming the raw material of the space into a series of ascetic sculptural propositions, ranging from half-filled plastic containers of dust, scrapings and mop water, all the way to an improvised house of cards composed entirely of fractured ceiling panels. The material wake of this show informed Simon’s following project, Everything is Medicine (2017), displayed at the Lily Brooke Gallery later that year; a progression further augmented by his exhibition at Castor Projects in early 2018, In From The Light, a somewhat ostentatious development in what Simon would later come to refer as his signature process of ‘decreation’: deconstructing exhibition spaces and using their residual matter to form artworks that are both emotionally affective and conceptually astute.

It was clear from our conversation that questions concerning matter, objects and materiality were prescient for Simon. In no uncertain terms, Everything Can Be Broken was a naked and direct exposition of the fundamental processes inherent to any artistic activity: bales of paint-stained rags, rows of unlabelled jam jars and Tupperware pots, ethers of plaster dust and shards of dried white emulsion. Of course, contemporaries of Simon have equally grappled with similar questions of labour, materiality and the mundane. The artworks of Susan Collis, James Balmforth or Mike Ballard come immediately to mind. There are also those who follow the path of materiality to what Quentin Meillassoux would call the ‘arche-fossil’: how–if at all–we are able to think phenomena and life before the emergence of thought itself:

'I start the engine of my car. Liquefied dinosaur bones burst into flame. I walk up a chalky hill. Billions of ancient pulverized undersea creatures grip my shoes. I breathe. Bacterial pollution from some Archean cataclysm fills my alveoli—we call it oxygen.'[1]

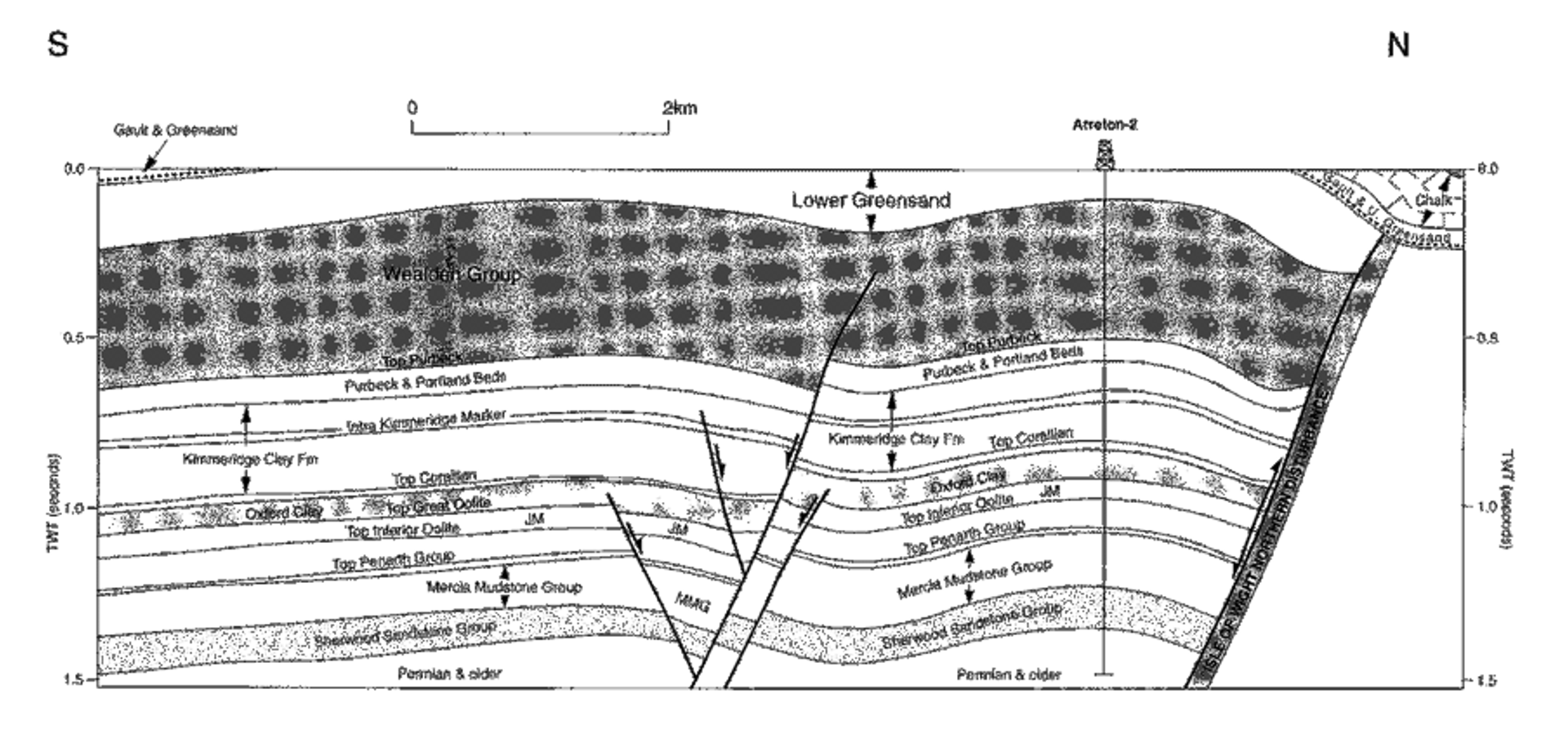

N-S geological cross-section depicting the occurrence of a major fault block terrace in the hanging wall of the Isle of Wight’s northern fault line.

Conversations concerning matter, objects or materials will invariably cross this chic cultural shibboleth: our enveloping misanthropic school du jour, the inherent capacities of matter per se. Waves of contemporary artists have risen to popularity through this post-anthropocentric lens, resulting in either a fascination in otherly forms of nonhuman life, or else a vision of the human subject as archaeological record, seen from the vantage of some far-off sci-fi VR spectacular. In their own ways rich, progressive, and often baffling artworks are produced in this namesake; one need only think of Eduardo Navarro’s Timeless Alex (2015), performed as part of the 2015 New Museum Triennial, in which Navarro wore a fake tortoise suit, crawled around a Manhattan rooftop and attempted to ‘reach a new state of psychic sensorium’ attuned to a now extinct species of Pinta Island tortoise, for evidence of this matter.

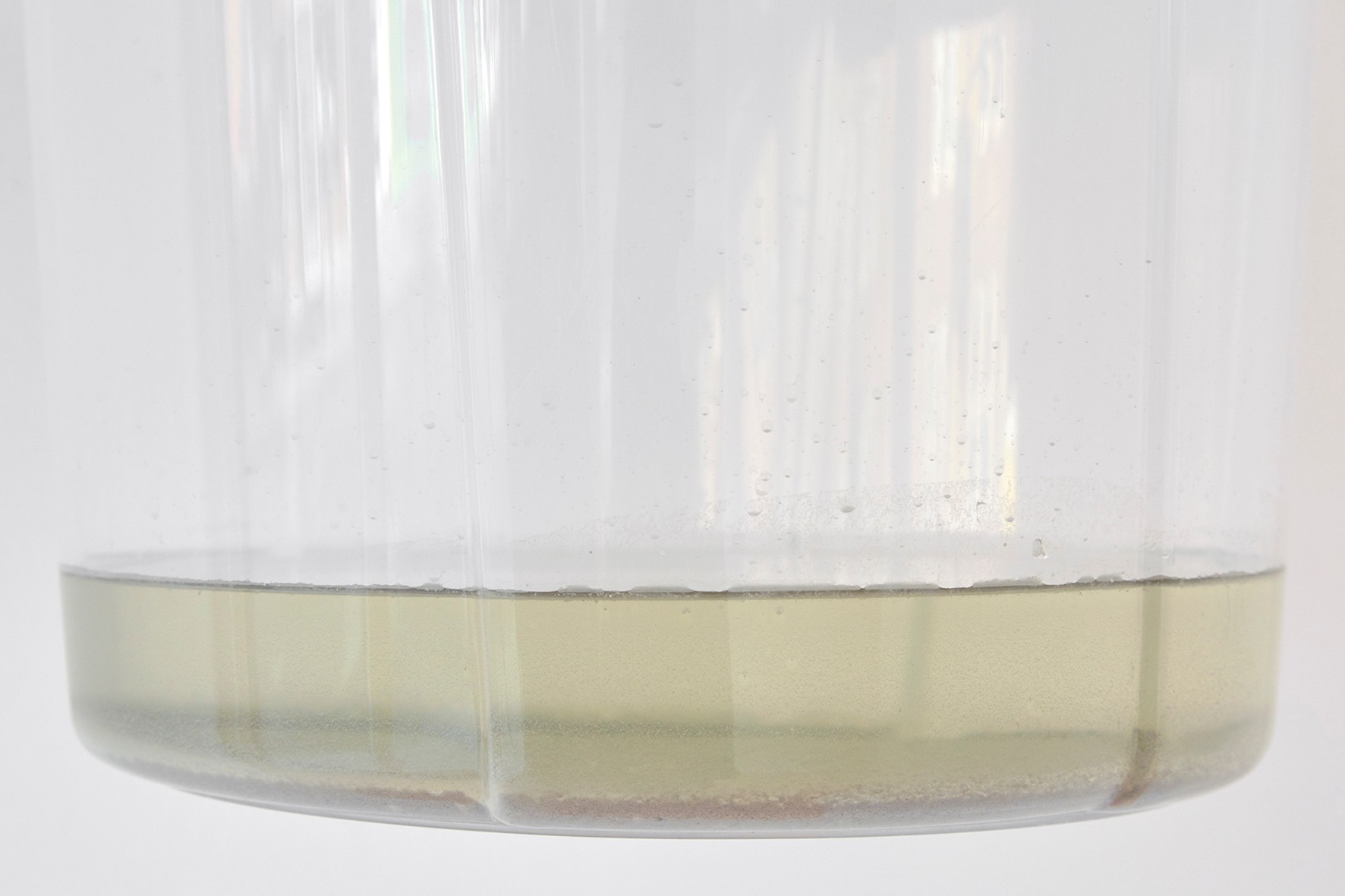

However, more important to Simon’s practice, and unique to it, was the matter of memory. Memory traversed our entire exchange that day, from the shores of his childhood to his grandfather’s photobook, the recollection of his past work in various shows and projects to the presence of his physical and haptic memory, preserved through paint splattered dust sheets, hand-dyed linens and a single bottle-chipped table. So too did memory fold, accumulate and coil through Simon’s own artworks. Not only were his works memorable, but they seemed to work with memory. In his studio Simon keeps tub after tub of dust, grit, clippings and fittings from previous locations where he has worked; a quick nod to those in which sat the Division of Labour, Lily Brooke and Castor Projects, and we were soon unveiling box after box of anonymous debris, rifling through stacks of neatly folded dyed-black textiles, unsheathing rubber galaxies of brick dust, metal shavings and clipped wires.

Indeed, it is no coincidence Simon cites the words and practice of Bruce Nauman as a major influence, quoting his famous line that, “if I was an artist and I was in the studio, then everything I was doing in the studio should be art. From that point on, art becomes more of an activity and less of a product.” Simon’s practice is concerned less with finished products than its process of development, his own development, and the memory of these activities in time. This, it would seem, has been the major lasting influence of Simon’s earlier collaborative practice with artist William Mackrell. Manifest as a series of often Herculean or Sisyphean performances, these happenings were enacted live and usually in competition, occasionally finding their leftover matter presented as sculptures or images, or as the residual membrane of later artworks. What was crucial in every case was the persistence of memory through time, and how it inevitably came to effectuate the real or present; the power of memory, so to speak, to act on our consciousness.

[1] Timothy Morton, Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World (Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2013) pp. 52.

Edition of 50

Designed by Mingo Mingo Studio

Produced by George Marsh

Published by William Bennington Gallery

Printed in London, 2019

Elam Publishing, London

Catalogue Essay

2018

Camberwell College of Arts, London

Exhibition Text

2018

Limbo Limbo, London

Exhibition Text

2017

Saatchi Art & Music Magazine, London

Review

2017

B.A.E.S., London

Exhibition Text

2016