Royal Academy of Arts Magazine, London

Article

2025

émergent, London

Interview

2025

C-Mine, Genk

Exhibition Text

2025

Hannah Barry Gallery x Foolscap Editions, London

Editor

2025

Lo Brutto Stahl, Paris & Basel

Exhibition Text

2024

Hannah Barry Gallery x Foolscap Editions, London

Editor

2024

émergent, London

Interview

2024

DUVE, Berlin

Exhibition Text

2024

émergent, London

Interview

2024

Incubator, London

Exhibition Text

2023

QUEERCIRCLE, London

Exhibition Text

2023

L.U.P.O., Milan

Catalogue Essay

2023

Tarmac Press, Herne Bay

Catalogue Essay

2023

Brooke Bennington, London

Exhibition Text

2023

Freelands Foundation, London

Catalogue Essay

2023

superzoom, Paris

Exhibition Text

2023

Lichen Books, London

Catalogue Essay

2022

Tennis Elbow, New York

Exhibition Text

2022

émergent, London

Interview

2022

Guts Gallery, London

Exhibition Text

2021

Kupfer Projects, London

Exhibition Text

2021

Collective Ending, London

Catalogue Essay

2021

L21 Gallery S’Escorxador, Palma De Mallorca

Exhibition Text

2021

TJ Boulting, London

Exhibition Text

2021

COEVAL, Berlin

Interview

2021

Quench Gallery, Margate

Exhibition Text

2021

COEVAL, Berlin

Interview

2021

COEVAL, Berlin

Interview

2021

Foolscap Editions, London

Catalogue Essay

2020

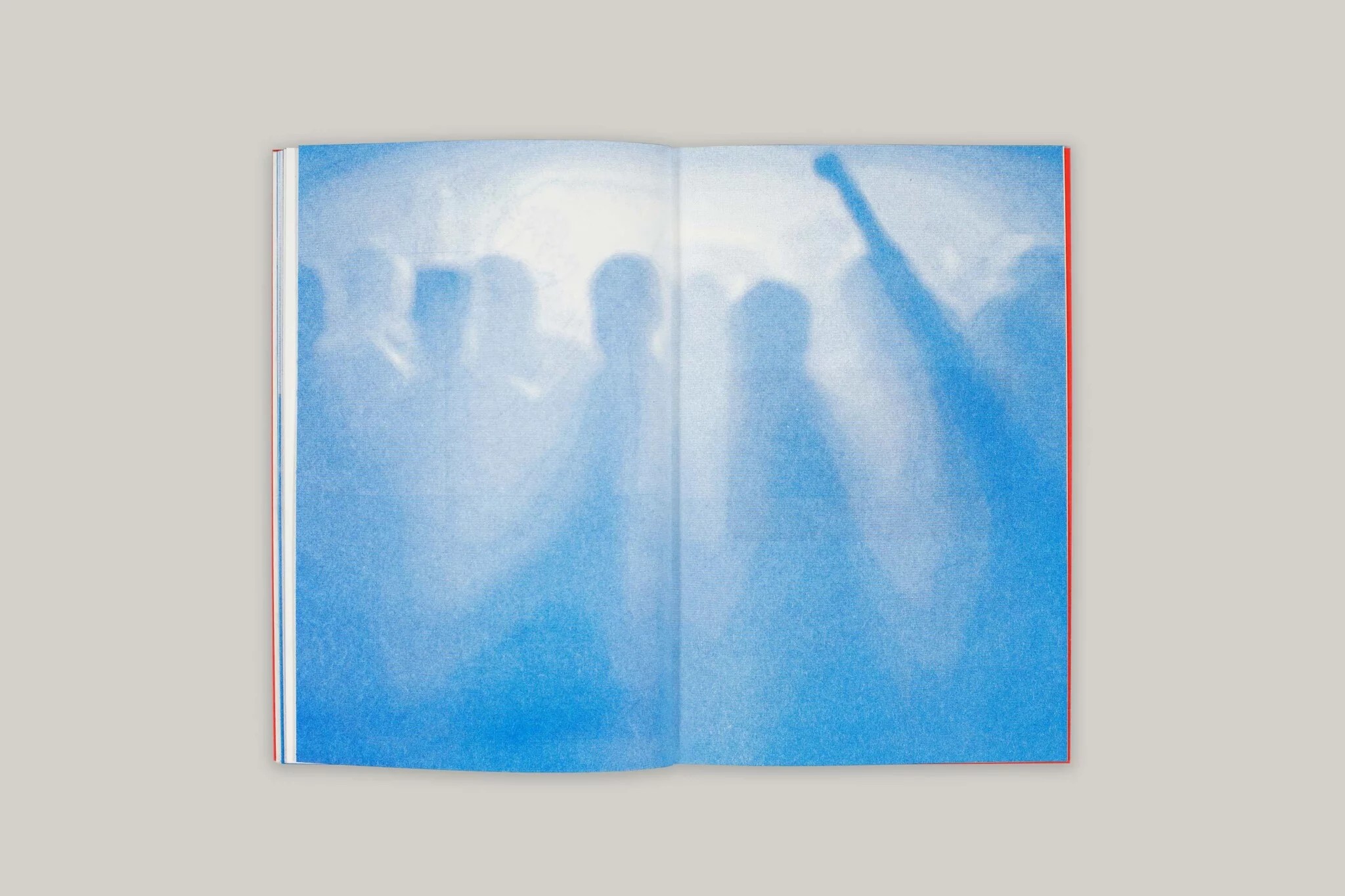

Raving without Nature

'The needle skipped the groove of the present.

Into this dark forest you have already turned.'

– Timothy Morton, Dark Ecology, 2016

In an epigraph to the 2011 anthology, Fanged Noumena – a collection of writings from influential British philosopher turned NRx poster boy, Nick Land – the late cultural theorist Mark Fisher quotes from Land’s mysterious essay, ‘No Future’, stating that the advent of UK Rave in 1988 was nothing less than our 'impending human extinction becoming accessible as a dancefloor.'[1] It was a proclamation that chimed with much of the cultural adrenalin of the decade: high-speed technology, cyberspace and cultural pluralism. Within the brief but emphatic years of 1988 - 1994, Britain ingested a burst of cultural, economic and technological amphetamine, leaving the population wired. A hysteria of alienating forces saw the emergence of algorithmic processing, a deregulated finance industry, post-industrial service economies, and the popular emergence of the home computer. It was a fever pitch of pre-millennial acceleration.

For Land, raving was a lucid expression of our nascent posthumanism, a place where identity fractured as we came to embody new cybernetic pleasures. Where the ruthless affectivity of our social alienation played out – drowning in a whirlpool of technology, the last breath of humanity gargling into the obscurity of acidic bass. A fascination with the more virulent aspects of runaway techno-culture led many to follow the descent of UK Rave into more ominous derivatives of what Simon Reynolds calls the ’90s ‘hardcore continuum’ – a sonic wormhole stretching from Doomcore to Jungle to Gabber. A world of sweat, dopamine and schizophrenia; where bodies are cannibalised and repurposed – rigged up through electrons, soundwaves and neurons; affects and FXs, DJs, mixers and Dip Dabs. These were the dark disciples of UK Rave, constituents of a culture hellbent on all-round mystical rapture: servants to euphoria.

Despite its proposed virulence, real oblivion was never much desired by ravers. Hidden within the pitch-tingling cri de guerre of UK Rave’s euphoric offspring – Acieed! – was a generative and propositional force. Land had been right when he challenged long-held assumptions of the social escapism of rave – the last in a long line of Dionysiac spaces, trimmed and hedged for the more morally sceptical and hedonistically driven amongst us. Of course, for many the ingrained fidelity between electronic music and narcotics has unquestionably turned rave into a sinister retreat from their daily lives – an arrested freedom. Living for the weekend is hardly a novel phenomenon in reaction to the drudgery of wage labour or diminished social securities, and as Michel Galliot states, raves 'may in this sense be as old as man himself.'[2]

UK Rave emerged in the foreclosure of Britain’s post-war social contract – it provided a home, a culture and a people, something the state chose no longer to provide. It emerged in the ashes of the Miners Strike, instantiated in the ruins of Britain's post-industrial past – hosted in abandoned grain silos, disused factories and military bunkers; forced into the rural pastures of England’s ‘green and pleasant land’. Nevertheless, it remains antithetical to me, to on the one hand suggest some kind of warped, metaphysical access to full-blown planetary meltdown, and on the other, a primitive form of long-standing social escapism. Could it be that – contrary to the hushed tones of stately conservatism – rave is less a question of escape and really, as Land saw in its ghostly inception, a question of access? But access to what – to each other? – to something outside? – to reality?

***

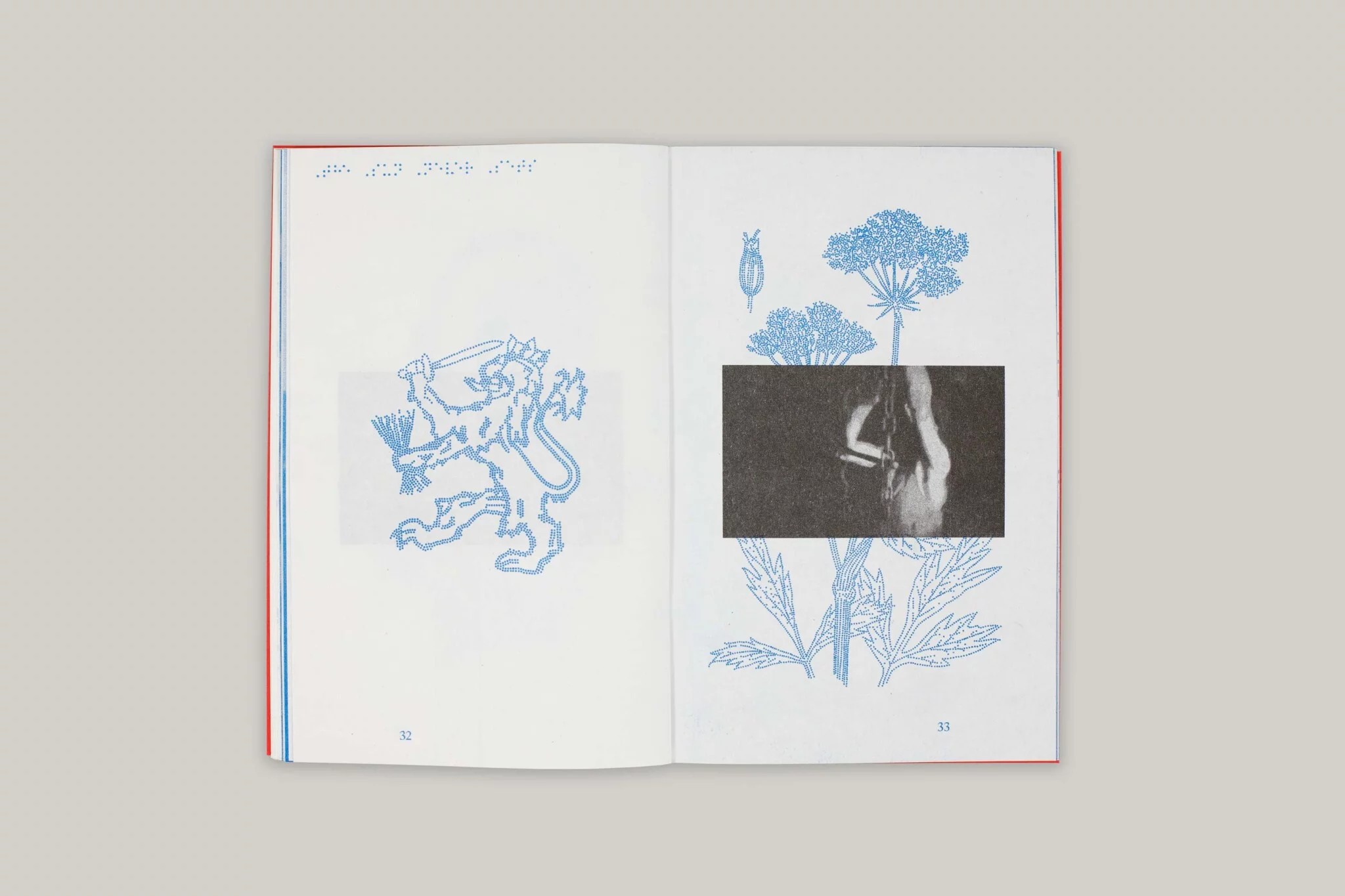

Looking at old rave flyers, you’d be forgiven for assuming this metaphysical overdose was geared toward a prior harmony with ‘Nature’. By the height of the first-wave of UK Rave (’88 – ’89) there were clubs named ‘Universe & Earth’ and ‘Land of Oz’. Each sporting self-styled Goddesses of Love distributing free fruit to their weary participants. Promoters such as Biology and Genesis used prints of L'Uomo Vitruviano or Laocoön and His Sons to advertise rave-events. Norway’s first ever techno superstar called himself Biosphere. In each case, the message is clear: the cosmological and childlike romanticism of a ‘return to Arcadia’. Throughout the history of rave, environmental concern was a large part of the counter-cultural zeitgeist. Ravers took to the fields. To the countryside. To the sun. Extending the end. It was a unified pilgrimage, the most sacred of all gatherings taking place in the woods, on a cliff top or on a boat. Environments uninterrupted by the law, free from pretence and glamour and wholly reliable on a collective experience.

But this was not the wilderness and beauty of Rousseau's ‘State of Nature’ – timeless, discrete and out-there. Individuals do not stand outside of the rave and look in, as Immanuel Kant would have you believe you do with Nature: the human mind as a rational agent – detached and intentional. What was clear to the pilled-up, jacked-up and loved-up cognoscenti of the ’80s underground was that, contrary to rock, the revolutionary potential of rave was not tied up in the monoethnic, carceral ‘authenticity’ of Liam Gallagher or Damon Albarn. Rave was not social realism. It was not natural nor a quest for some authentic past to which we should return. There was nothing to be told to us – mirrored back to us; to show us ‘what Britain is supposed to look and feel like’. They knew, as we do, that the magic lied in the fact that 'rave constructs an experience.'[3]

There is indeed something arcane – ancient about raving; 'A Pastoral beat of the blood' as Welsh poet Dylan Marlais Thomas once wrote. The four-to-the-floor kicks, phosphorescent strings and toffee-like continuas of bass, overlaid with the ethereal yet bubbling orgasma of abstracted feminine moans. The pulse. The organic world is filled with rhythms and energies: the entropic rotation from Summer to Winter Solstice, the ebb and flow of rivers, landscapes and ecosystems. A life-cycle of desolation and rebirth; sex, intensity and death. For millennia we have engaged in practices of collective effervescence – attuning ourselves to the rhythms of life and to anonymous forces. We make ritual, dance and sacrifice. Connect with the Other – the abject feeling that one is surrounded and penetrated by other entities: solar radiation, viruses, stomach bacteria, parasites or mitochondria – not to mention other humans.

Raving is an uncanny and eerie experience of – ‘Nature’of the Other, the not-present. And why is it disturbing? Because you are already living on more than one timescale, through more than one organism, mode of perception or language. Where many have successfully pointed beyond the individual in moments of collective ritual – moments when society produces sacredness – these are all too frequently attributed to a ‘higher power’ or transcendent force – to God, the subject or history. Raving goes beyond this – it is the dawning realisation of the human species: that they are in fact, and always have been, part of—and inside of—something larger than themselves. Something alive. Something imperceivable. Something truly terrifying. 120bpm: the average heartbeat of a developed foetus inside its mother’s womb.

***

Raving is a spectral game. Lost in a frenzy of euphoric shape-shifting, dancers are no longer isolated Subjects, skipping through the dandelion meadow. Rave shatters the illusion that there is something fundamentally different about us ‘in here’ and the world ‘out there’ – the banal platitude of humdrum ‘reality’. Fully immersed on the dance floor, bodies are no longer fleshy lumps of tissue and bone detached from the mind. They are portals. Wormholes to a pre-personal continuum of intensity, a decentralised and non-hierarchical cybernetic system melding technology, matter and affect into one horizontal flow of collective acceleration: lights/wavelengths, drugs/hormones, clothes/textures, mixers/frequencies, dancers/bodies, 'a continuous, self-vibrating region of intensities whose development avoids any orientation toward a culmination point or external end.'[4] Objects of desire are replaced by libidinal drives. Tempos devoured by pure speed.

Space and time become twisted. Tracks evolve without narrative. Emotions surge forth without aim. Sonorous molecules percolate to infinity. Ravers no longer notice the lights, the other ravers or the music as separate elements but feel them as one intense event: sites of production where different flows of energy link together within an ever-changing infrastructure. An immanent plane of proto-subjective soup that connects a hand cocked like a pistol to a Kenwood subwoofer; a rush of dopamine to the neon glow of a UV blacklight. In this sense, raves are an assemblage of what philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari would call ‘desiring-machines’. During a rave set, common human experiences of an other-worldly time – epileptic fits, daydreams, un petit mal – are accelerated and intensified, consciously desired. We chase sensations of vertigo and disorder as sources of pleasure. The psychic equivalent of the strobe’s stop-gap photography effect. A lapse in consciousness – as if your body was suddenly operating on someone else’s time.

Raving couldn’t be further from ideas of escapism or exteriority. It’s about making connections. A drive – not only to access but to be accessed. Raving is a network – of serotonin, mud-caked trainers, sub-atomic bass-waves and gnashing jaws. It is neither human nor unhuman, organic or inorganic. It’s as much about wanting to embed ourselves in the rhythm of ‘Nature’ as it is allowing flows of all kinds – electronic, electromagnetic, interpersonal, organic, chemical, pharmaceutical – to enter us, through us, and into the next. The shrink-wrapped subjectivity that we covet so dearly almost floats around outside of oneself, endlessly warped and permeable to the collective flows of rave’s ecological highs. Frightened, as we all are, of the insidious poverty of our day-to-day ‘reality’, raving is a mode of being which is always-already more-than-one. It is the realisation that what we take for ‘Nature’ and ‘human’ are spectral qualities, effervescent and irreducible, glittering with porous borders and affective flows. Cogs in the machine of posthuman becoming.

[1] Nick Land, ‘No Future,’ in Fanged Noumena: Collected Writings 1987 – 2007 (Falmouth: Urbanomic, 2011) pp. 398.

[2] Michel Galliot, Multiple Meaning: Techno - an artistic and political laboratory of the present – interviews with Jean-Luc Nancy and Michel Maffesoli (Paris: Dis Voir, 1998) pp. 23.

[3] Simon Reynolds, Energy Flash: A Journey through Rave Music and Dance Culture (London: Picador, 1998) pp. xix.

[4] Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2005) pp. 2.

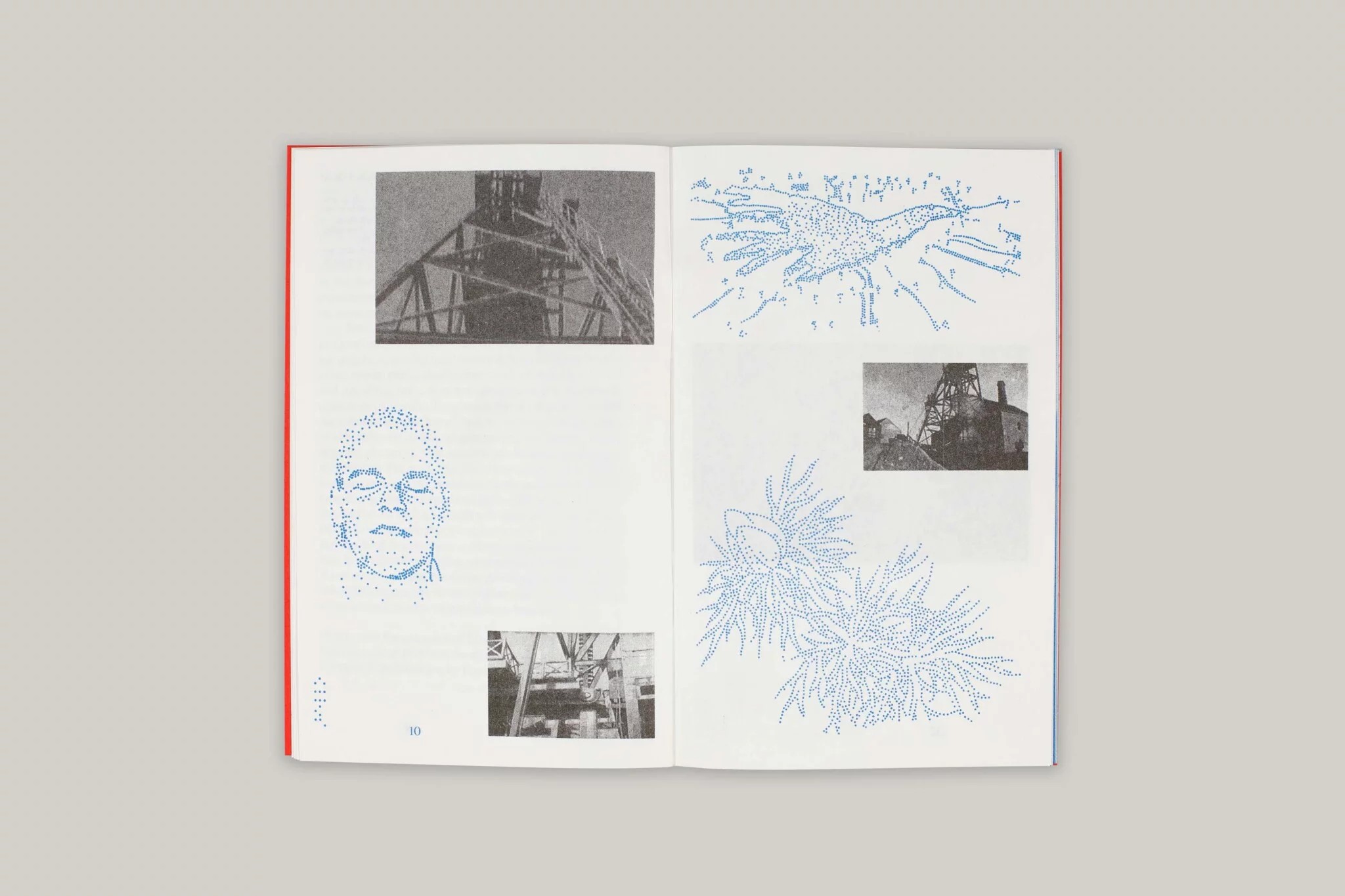

Page Count: 56 p.p.

Size: 125 x 194mm

Print Method: 2 Colour Risograph (Red or Blue Variation)

Cover: 2 Colour Silkscreen with 3M Reflective Ink

Bind Method: Saddle Stitch

ISBN: 978-1-9997990-5-2

Edition: 250

Published: 1st Edition September 2020

Gentrified Underground, Zurich

Catalogue Essay

2020

Camberwell College of Arts, London

Exhibition Text

2019

Kronos Publishing, London

Editor

2019

Elam Publishing, London

Editor

2019

William Bennington Gallery, London

Catalogue Essay

2019

Elam Publishing, London

Catalogue Essay

2018

Camberwell College of Arts, London

Exhibition Text

2018

Limbo Limbo, London

Exhibition Text

2017

Saatchi Art & Music Magazine, London

Review

2017

B.A.E.S., London

Exhibition Text

2016