Royal Academy of Arts Magazine, London

Article

2025

émergent, London

Interview

2025

C-Mine, Genk

Exhibition Text

2025

Hannah Barry Gallery x Foolscap Editions, London

Editor

2025

Lo Brutto Stahl, Paris & Basel

Exhibition Text

2024

Hannah Barry Gallery x Foolscap Editions, London

Editor

2024

émergent, London

Interview

2024

DUVE, Berlin

Exhibition Text

2024

émergent, London

Interview

2024

Incubator, London

Exhibition Text

2023

QUEERCIRCLE, London

Exhibition Text

2023

L.U.P.O., Milan

Catalogue Essay

2023

Tarmac Press, Herne Bay

Catalogue Essay

2023

Brooke Bennington, London

Exhibition Text

2023

Freelands Foundation, London

Catalogue Essay

2023

superzoom, Paris

Exhibition Text

2023

Lichen Books, London

Catalogue Essay

2022

Convulsive Beauty

'Beauty will be convulsive or not at all.'

– André Breton, 1928

— Extract —

Already in its embryonic years, the subject of surrealism was deeply folded into discourses of style and iconography. On the one hand were proponents of automatism and irrational spontaneity, and on the other, illusionistic and oneiric depictions – as seen in the contrasting practices of Masson’s early Automatic Drawings and the phantasmic 'paranoia-criticism' of Dalí, Ernst or Magritte. It is with this in mind that André Breton, author of the First Manifesto and arguably the greatest spokesperson for surrealism, introduces how best to aesthetically conceive of the unconscious as a site of both psychic conflict and social contradiction, two of its quintessential concerns as an aesthetic and political device. Known as 'convulsive beauty,' in this treatise, Breton offers no clear route to a comprehensive style of surrealism, rather produces a series of internal contradictions, each of which strike me as present in Lucas’ work – but are themselves incommensurable.

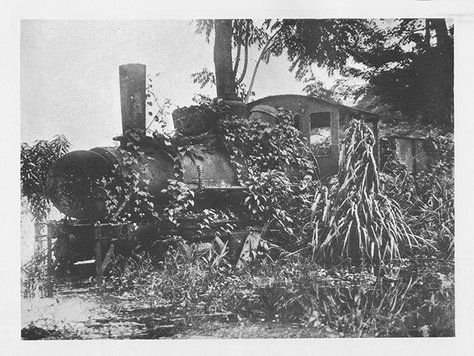

Given his aversion to the ‘the real forms of real objects,’[1] and the necessary role of surrealism in insisting another order of experience, it is with surprise that Breton first introduced ‘convulsive beauty’ with the ‘realist’ medium of photography. Writing in the opening pages of his 1937 book, L’Amour fou, Breton recollects a strange missing photograph, described as a 'speeding locomotive abandoned for years to the delirium of a virgin forest.'[2] It is a powerful thought, made all the more compelling as an image 'for having not being pictured'[3] – so writes the book’s English translator, Mary Ann Caws. However, the photograph did exist and was in fact reproduced later that same year in Minotaure, where it accompanied Benjamin Péret’s text, 'La nature dévoure le progress et le dépasse.'

Anonymous photograph reproduced in Minotaure, 1937

It appears easy to read this image, and therefore its conceptual inference, as symbolising the unabating tension between nature and culture – the imperial wrought of civilisation punctuating the 'heart of darkness,' the vital plenitude of nature taking its revenge, the wildness of the unconscious pitted against the imperatives of the taming mind. Surrealism, especially in Paris, had always been securely sited in the city, and often expressed a fascination with its respective “other”: nature at its most extreme – desert, forest and jungle. This can be seen most clearly in Ernst’s Forest paintings of the late ’20s, which display a clear tradition of German Romanticism in their celebration of the excesses of nature, liberating us from the limitations of reason and culture; or in Frederick Sommar’s Arizona Landscapes, showcasing the banal severity of nature’s arid lands through brute American formalism.

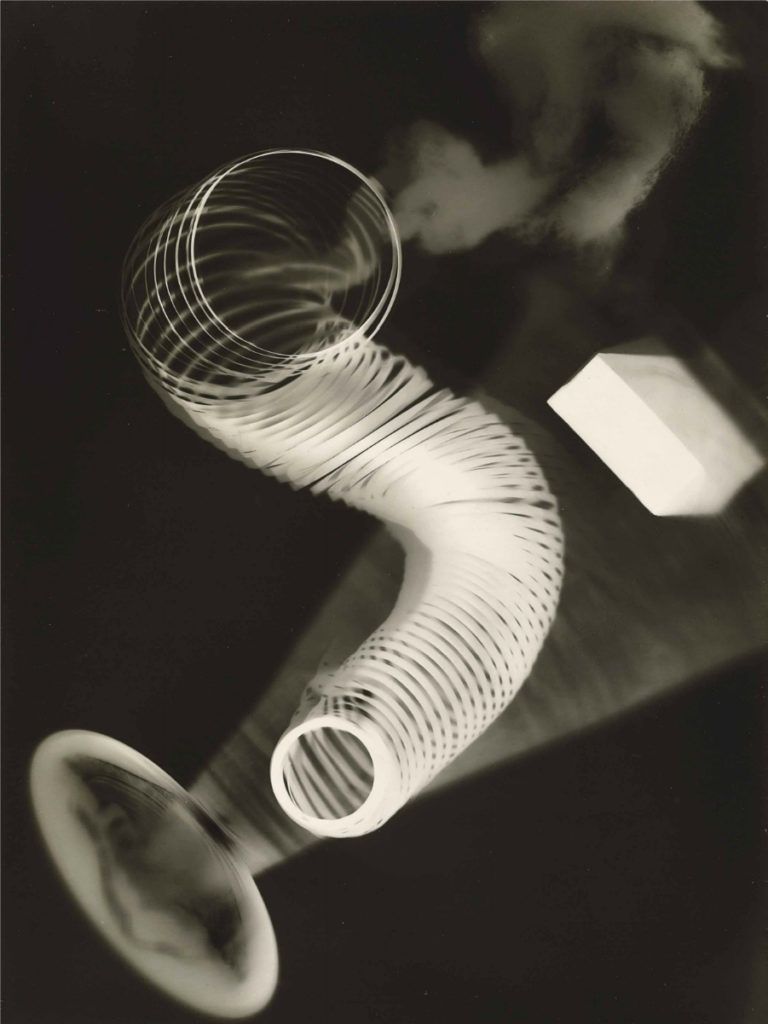

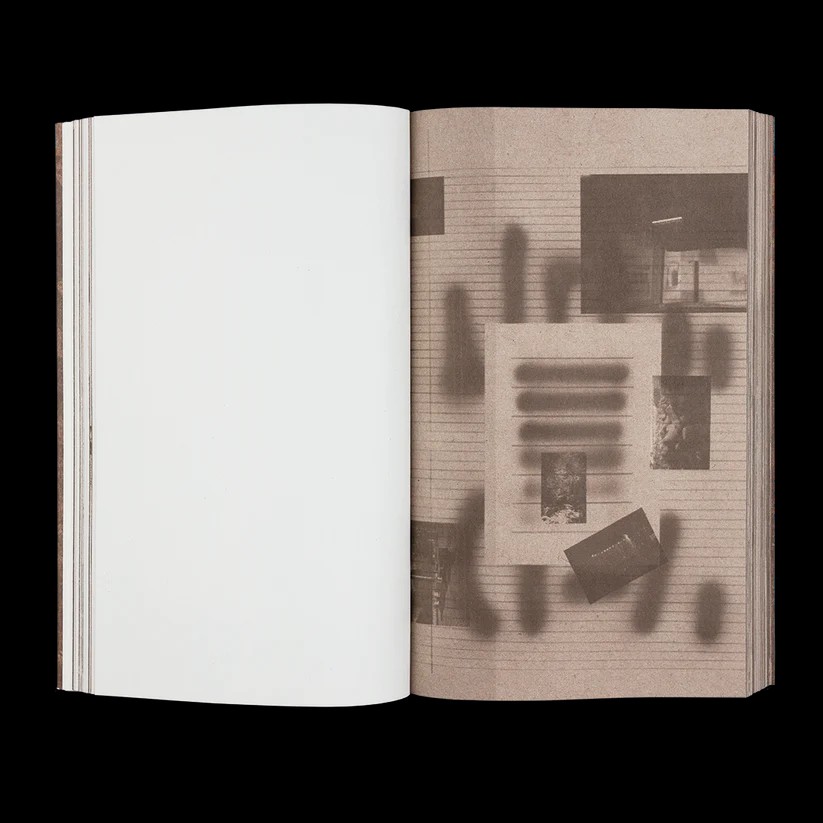

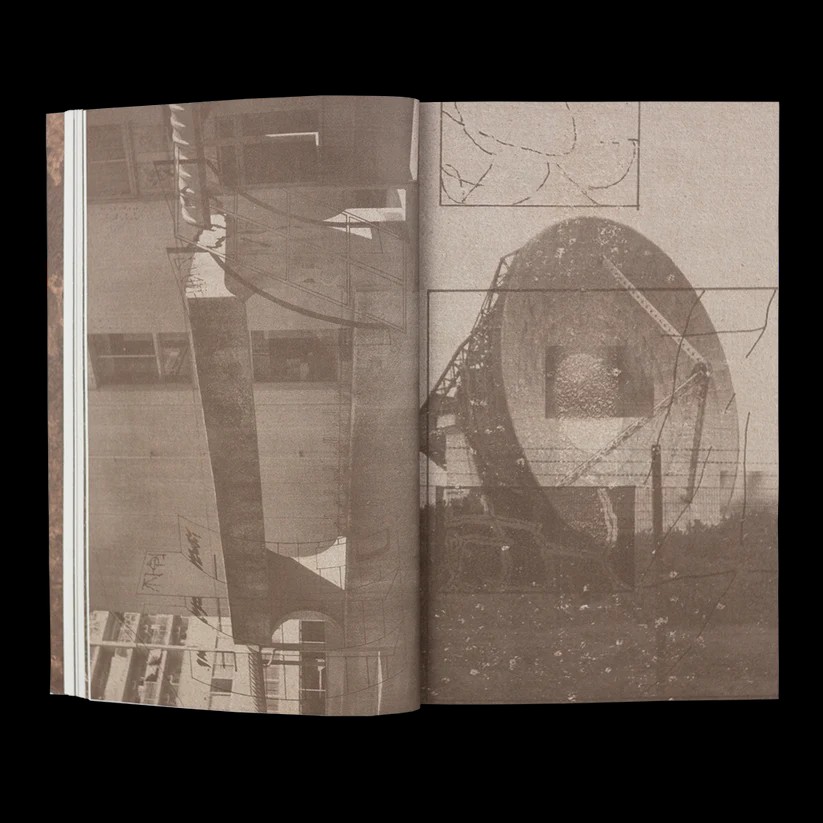

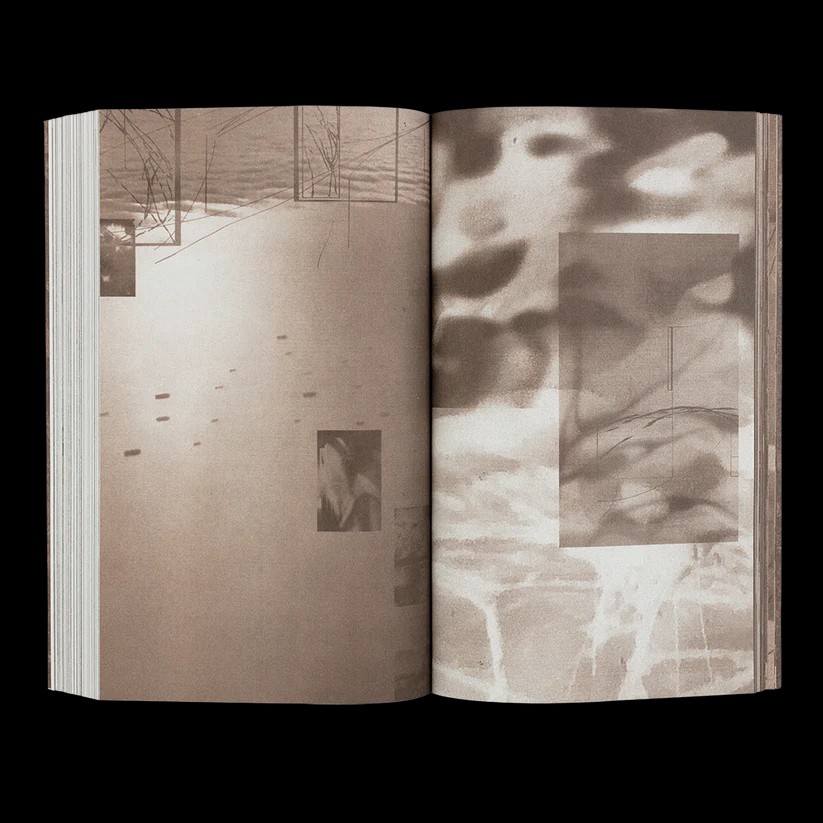

It is clear to see the same divisions at work in this book, between the industrial facades of city architecture and the incursions of an unnamed and disruptive other. Not only are structures in Dupuy’s photographs crawling with trees, overgrown with bushes and reeds, but the images themselves appear to be overshadowed by silhouettes of organic life, as if unknown organisms were hovering above the page in pure exteriority to the image. In these moments, Dupuy’s work reminds me of another pioneering surrealist, Man Ray, and his 'rayographs', in which objects are placed directly on a sheet of photosensitised paper and exposed to light. The result is the eerie sensation of an unknown agency lingering somewhere above or within the image: a force conjured out of nothing, shivering between perception and representation.

Man Ray, Untitled rayograph, 1922

These key contradictions – between nature and culture, image and exteriority – are indeed integral to Dupuy’s work. Nevertheless, for Breton, beauty’s 'convulsiveness' does not linger at these junctions for long. The directness of the photographic image and its materiality must be accompanied with a deeper problematising of reality and the ordering principles of reason that constrain it. Indeed, it is precisely because of its realist tendencies that photography is best places to distort appearances and force a rupture in the surface of perceived reality. For as he writes in L’Amour fou, 'Convulsive Beauty will be veiled-erotic, fixed-explosive and magical-circumstantial or will not be.'[4] Famously cryptic, this description nevertheless provides clues from which to approach the images in this book and their relationship to the greater principles of surrealism.

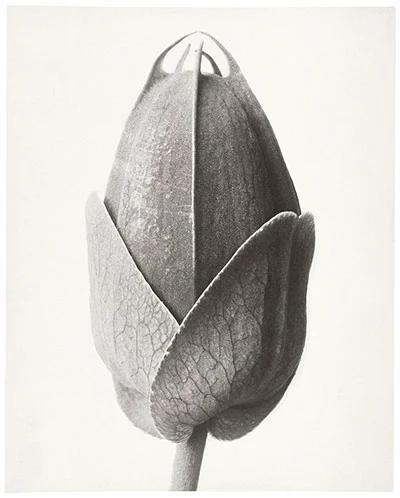

The 'veiled-erotic,' Breton goes on to explain, can be seen in forms of natural mimicry, including examples such as a limestone deposit shaped like an egg; a quartz wall formed like a sculpted mantle; or a coral reef that appears like an underwater garden.[5] In each case, we see that natural form and cultural sign are intermingled, in material form but also semiotic juxtaposition; a confluence often captured by the blind instrument of the camera, for example, in the Brassï photographs of 'involutory sculptures' or Karl Blossfeldt’s photographs of flowers that resemble architectural forms – both of which find a resonance in Dupuy’s images, which through their own language blur the significations of organic and inorganic forms, creating a scenario where it is difficult to infer the man-made from the natural, or as Breton importantly states, where 'the animate is so close to the inanimate.'[6]

Karl Blossfeldt, Passion Flower Bud, c. 1910 – 1928

This tendency is inversed and compounded through the 'fixed-explosive,' the expiration of motion seen in photography, where 'rather than the spontaneous action of the inanimate become animate, we have the arrested motion of a body become an image.'[7] And finally, it is extrapolated in the 'magical-circumstantial', otherwise known as the trouvaille, or the happy accident of objective chance. It is in this mode, as it is in Breton’s novels and surrealism more generally, that objects appear to us as 'rare', places become 'strange', meetings 'sudden', and yet all of these scenarios are haunted by an eternal return, a compulsive and anxious repetition – experienced as such, in turn, as we shift through the many pages of this book, encountering eerie after eerie manifestation of a distant yet strangely familiar world.

For art critic Hal Foster, it is here – at the precipice between life and death, future and past – that convulsive beauty brushes up against the uncanny, suggesting an important and compulsive dimension of surrealism. In his 1993 book, Compulsive Beauty, Foster argues that this tension is best understood as a dynamic which foregrounds 'the primacy of death, the primordial condition to which life is recalled.'[8] This can be seen in the petrified nature so prevalent in the images described by Breton, and to which we shall add the bleached lichen that silently breed across Dupuy’s images, like varicose veins across human skin – scanned, embedded and binarised in the image, they are at once an emergent vitality but also the inertia of cosmic entropy: 'it grows but only, in the guise of death, to devour the progress of the train, or the progress that is once symbolised.'[9]

For Dupuy, the expiration of progress symbolised in this book, and in his work more generally, can be read through the concept of hauntology – that of our lost futures and the spectral insistence that the promises of our past have increasingly been denied to us – that the modernist architectures captured across these pages, once exemplary forms of a future-yet-to-come, have been made strange, eerie in their lack of agency and in their disturbing movement from shared icons of optimism to spectres of deep portension. As if the lichen that crawls across their facades, itself a prolific consumer of past ruins, has undergone a blinding trauma or photographic shock – one that has petrified it, reducing it – and with it, 'the tantalising ache of a future just out of reach'[10] – to an indeterminate state between life and death, as evocative of thriving algae as it is of perished coral.

The affects of hauntology have informed Dupuy’s work, not only through his more recent reading of figures such as Mark Fisher and Simon Reynolds, but through an optical nerve of forward-thinking electronic music and cyberpunk video games, of which he has been engrossed since a young age. It is no surprise that labels such as Hyperdub, Basic Channel and Warp were central to his musical upbringing. Aesthetically, the spectral and post-industrial overtures that one hears in Burial, The Spaceape and Autechre provoke the same arrested eroticism, melancholy and temporal distortion that one sees in surrealist photography. They reflect, on the one hand, the increasing fragmentation and dispossession of social life, and on the other, 'a generation born into that ahistorical, anti-mnemonic blip culture—a generation, that is to say, for whom time has always come ready-cut into digital micro-slices.'[11]

[1] André Breton, Surrealism and Painting (1928) trans. Simon Watson Taylor (New York: Harper & Row, 1972), p. 4.

[2] André Breton, L’Amour fou (1937), trans. Mary Ann Caws (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1987), p. 10.

[3] Mary Ann Caws, notes to Breton, L’Amour fou, p. 124.

[4] Breton, L’Amour fou, p. 19. 5 Ibid., p. 10 – 13.

[5] Ibid., p. 10 – 13.

[6] Ibid., p. 11.

[7] Hal Foster, Compulsive Beauty (Massachusetts: MIT Press, 1997), p. 27.

[8] Ibid., p. 25.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Mark Fisher, “London After the Rave” in K-Punk (online, 14 April 2006).

[11] Mark Fisher, Capitalist Realism (Winchester: Zero Books, 2009), p. 25.

264 pages

80gsm Uncoated Holmen Book Cream Inner Pages

300gsm Munken Pure Cover with Orange Foil

Printed black and PMS 8022 throughout

Section Sewn

Edition of 350 copies

Published by Lichen Books, 2022

Tennis Elbow, New York

Exhibition Text

2022

émergent, London

Interview

2022

Guts Gallery, London

Exhibition Text

2021

Kupfer Projects, London

Exhibition Text

2021

Collective Ending, London

Catalogue Essay

2021

L21 Gallery S’Escorxador, Palma De Mallorca

Exhibition Text

2021

TJ Boulting, London

Exhibition Text

2021

COEVAL, Berlin

Interview

2021

Quench Gallery, Margate

Exhibition Text

2021

COEVAL, Berlin

Interview

2021

COEVAL, Berlin

Interview

2021

Foolscap Editions, London

Catalogue Essay

2020

Gentrified Underground, Zurich

Catalogue Essay

2020

Camberwell College of Arts, London

Exhibition Text

2019

Kronos Publishing, London

Editor

2019

Elam Publishing, London

Editor

2019

William Bennington Gallery, London

Catalogue Essay

2019

Elam Publishing, London

Catalogue Essay

2018

Camberwell College of Arts, London

Exhibition Text

2018

Limbo Limbo, London

Exhibition Text

2017

Saatchi Art & Music Magazine, London

Review

2017

B.A.E.S., London

Exhibition Text

2016