Royal Academy of Arts Magazine, London

Article

2025

émergent, London

Interview

2025

C-Mine, Genk

Exhibition Text

2025

Hannah Barry Gallery x Foolscap Editions, London

Editor

2025

Lo Brutto Stahl, Paris & Basel

Exhibition Text

2024

Hannah Barry Gallery x Foolscap Editions, London

Editor

2024

émergent, London

Interview

2024

— Extract —

Charlie Mills: German for ‘broken horse’, for me the exhibition title, Gebrochenes Pferd, alludes to several significant genealogies. Firstly, to the rebellious spirit and formal mélange of Dada, which itself has the French etymology of ‘hobby horse’. Secondly, to Freud’s notorious case of Little Hans—a young boy whose phobia of horses was used by Freud to instantiate his theory that unconscious anxiety is displaced onto harmless external objects. Where did the title for the show come from? And how do you conceive of the horse, the motorbike and other key motifs in your work?

Alexandra Bircken: Horses as a metaphor for transport and traffic, for locomotion, power, elegance and dynamism have accompanied my work for a long time and have often been used as a counterpoint to the motorbike, the so-called ‘modern’ horse, in my installations. Recent research on this began in 2021, when I prepared for a sculpture in public space for the city of Munich. Munich, like many other western cities, is plastered with equestrian statues that almost exclusively portray male dominance and are an expression of our centuries-long patriarchal systems. Equestrian statues are always about power, war, dominance and winning, and are a purely male affair, with a few exceptions, such as Joan of Arc on horseback in Chignon. In every case it is about power communication. The rider represents the apparatus of power. I wanted to break with this form of representation and with what is associated with it: A Broken Horse.

My work Gebrochenes Pferd (Broken Horse) (2024), which will be exhibited at Maureen Paley, is a slightly modified, scaled-down version of the work in Munich. The horse is divided into two parts. A break has taken place, so to speak, and the horse comes to a standstill. This break symbolically takes it out of the power structure and brings it into the nursery. The front and rear parts of the horse are connected with a hinge and offer the possibility of resurrection. In Max Ernst's work, the horse appears again and again in the form of Loplop, whereby the word Loplop – as I called my motorbike swing which I showed at Secession in 2019 – is actually a children's word for gallop, coined by Max Ernst's son. Onomatopoeic.

It is interesting you mention the rider as an apparatus of power. The human body is intricately related to the subjects and discourses you describe, as is often the means by which our fears and desires – for some, fetishes – for empowerment, velocity, arrest and domination are brought to bear. And so, it is the human body, or perhaps its absence, which I am most drawn to in this dual presentation. How are you thinking about the human body itself in relation to these ideas - where has the rider gone?

The body seems to be dissolving: a motor can imitate the lever action of the human body, and so our interest is now focused primarily on imitating the brain. But women still have their periods and children are still born from the body cavity. It's a paradox. I'm less interested in the representation of the body right now; less motivation to depict it, at most in resolution. Maybe I’m past the body. The interwoven cable harnesses in the works Autobiography (2024) and Automatic (2024) are witnesses to this dissolution. The complex cable systems, which were the central nervous system responsible for raising and lowering the car windows, moving the windscreen wipers and all the other electronically-controlled functions of a car, have been stripped of their function. The car – understood as a kind of human prosthesis – was their host. A new system is created in the form of a condensed cable fabric, a kind of barcode or part DNA of a machine that no longer functions.

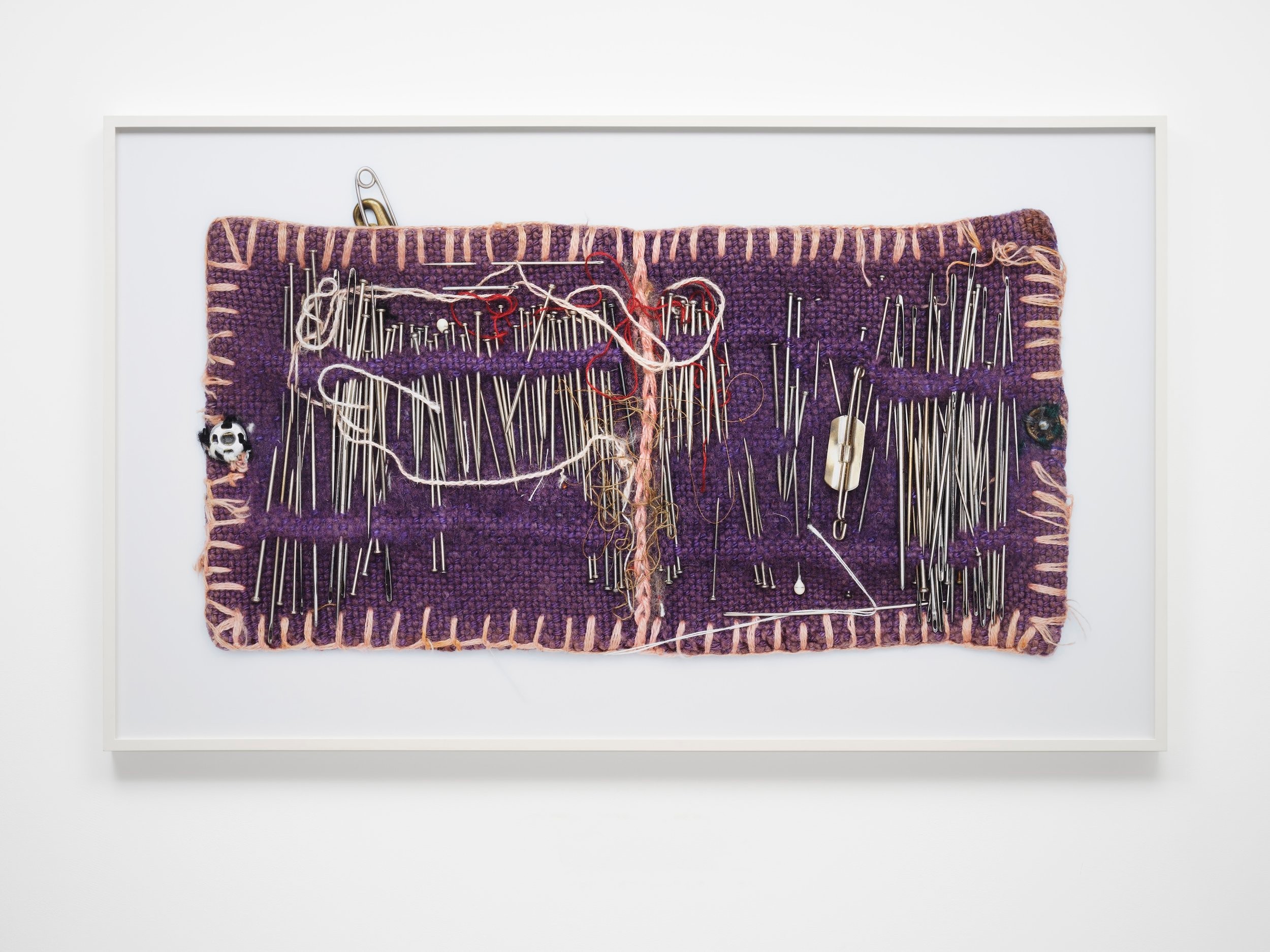

For me, these two works are interesting in that despite their abstraction they continue to evoke and allude to the body. Not least because some are composed of car cable harnesses, the nervous/vascular system of the vehicle, but because they betray your ongoing fidelity to techniques of knit, weave, drapery and hosiery - processes instinctively related to fashion and the production of wearable fabrics. For those who are not aware, can you tell us a bit about your background in the fashion industry and how it informs the works you will make in this exhibition?

In the years that I studied fashion and worked as a designer, I studied the human body intensively. The human body is sculpture in motion. My practice was essentially about dressing it and pursuing my interest in reinventing form and identity. I have intensively researched techniques for producing fibres and the possibilities of linking them into a coherent fabric. Every materiality already makes a statement and is a way of making a statement, a means of communication. At some point, removing materiality from the body and placing it alone in a space interested me more as a form of expression than the connection between body and materiality. In fashion, the body is not simply a body but always a social construct of beauty—a tight fitting corset. In fashion, the body is also a vehicle for transporting ideas, whereby the body and the tight corset of an idea of beauty must always dominate. At best, this expresses contemporaneity. In this sense, fashion fulfils a function. Art, on the other hand, has no function. I'm a fan of that.

What I find so compelling about this story is how fashion – an industry known for its exaltation of haute culture, luxury products and brand identity – in this case has led to a complete dismantling of traditional hierarchies in your work through a deeply materialist focus on the relationship between our bodies, its ‘second-skin’ and the various modern prosthesis we embed ourselves within; often with sparsely veiled eroticism, and at times a deliberate drive toward new forms of desire, pleasure and violence. In this sense I know you are inspired by the radical artist Leigh Bowery - how has your engagement with their work shaped your approach to art?

I once saw Leigh Bowery in a London club in the late 80s and was completely mesmerised by his appearance. As well as playing with different identities with extremely elaborate costumes, I was particularly fascinated in his reinvention of body shape and contours. A reimagining of aesthetics. A rewriting of our viewing habits and a reimagining of the concept of beauty. The breaking of many taboos was inherent in his appearances, in the costumes and performances. I think I took something of that with me. Indeed, this relationship between the body, materiality and its construction space is explored in several pieces installed across the two galleries, albeit in less graphic style. This includes a mirror of objects related to the dissected bodies of human prostheses, as you mentioned previously, including a stainless-steel bicycle seat at Maureen Paley and a windscreen and mudguard in chromed finish at Herald St. For me these works push the exhibitions from a sculptural into an environmental format.

The first mirrors used by humans were most likely pools of still water, or polished stones. Humans were always drawn to their reflection to grasp their own image and to gauge their own effect. Yet a mirror, or a looking glass, as it used to be called, can also be highly irritating as it plays with our senses. For instance, a mirror is an object that only becomes visible through the reflection of the objects that it reflects in its even surface. A mirror on a wall in an empty white cube is hardly visible, as its reflections and its surroundings are equal. For these reasons I like to implement mirrors in my work and installations. They unsettle the coherence and visual logic of an environment and of an object. They unsettle the viewer.

I can control the form of an artwork like the bicycle saddle, but I cannot control the environment which inscribes itself onto the mirrored surface as it travels through the world and is exhibited here and there. The work itself acquires a surreal, almost ephemeral quality and becomes hard to grasp as an object. The mirrored windshield and mudguard are part of a half BMW bike. Usually a see-through component of a generic bike. In its mirrored state it is devoid of its function and acts like a repellent to our glance.

DUVE, Berlin

Exhibition Text

2024

émergent, London

Interview

2024

Incubator, London

Exhibition Text

2023

QUEERCIRCLE, London

Exhibition Text

2023

L.U.P.O., Milan

Catalogue Essay

2023

Tarmac Press, Herne Bay

Catalogue Essay

2023

Brooke Bennington, London

Exhibition Text

2023

Freelands Foundation, London

Catalogue Essay

2023

superzoom, Paris

Exhibition Text

2023

Lichen Books, London

Catalogue Essay

2022

Tennis Elbow, New York

Exhibition Text

2022

émergent, London

Interview

2022

Guts Gallery, London

Exhibition Text

2021

Kupfer Projects, London

Exhibition Text

2021

Collective Ending, London

Catalogue Essay

2021

L21 Gallery S’Escorxador, Palma De Mallorca

Exhibition Text

2021

TJ Boulting, London

Exhibition Text

2021

COEVAL, Berlin

Interview

2021

Quench Gallery, Margate

Exhibition Text

2021

COEVAL, Berlin

Interview

2021

COEVAL, Berlin

Interview

2021

Foolscap Editions, London

Catalogue Essay

2020

Gentrified Underground, Zurich

Catalogue Essay

2020

Camberwell College of Arts, London

Exhibition Text

2019

Kronos Publishing, London

Editor

2019

Elam Publishing, London

Editor

2019

William Bennington Gallery, London

Catalogue Essay

2019

Elam Publishing, London

Catalogue Essay

2018

Camberwell College of Arts, London

Exhibition Text

2018

Limbo Limbo, London

Exhibition Text

2017

Saatchi Art & Music Magazine, London

Review

2017

B.A.E.S., London

Exhibition Text

2016